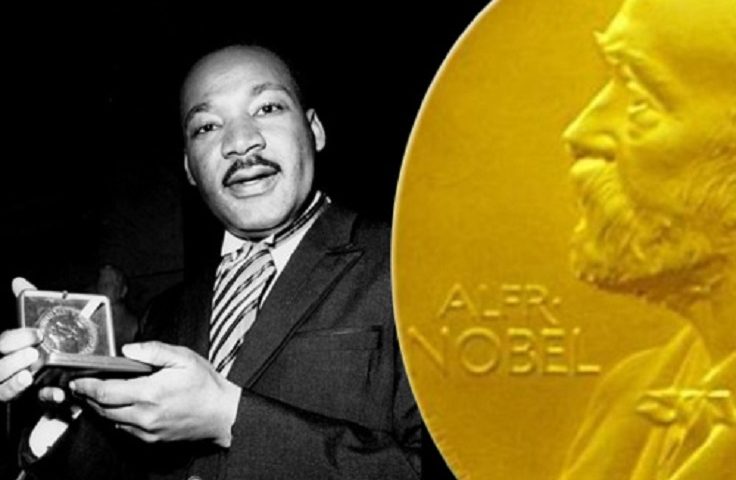

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Gunnar Jahn*, Chairman of the Nobel Committee on 10 December 1964

Not many years have passed since the name Martin Luther King became known all over the world. Nine years ago, as leader of the Negro people in Montgomery in the state of Alabama, he launched a campaign to secure for Negroes the right to use public transport on an equal footing with whites.

But it was not because he led a racial minority in their struggle for equality that Martin Luther King achieved fame. Many others have done the same, and their names have been forgotten.

Luther King’s name will endure for the way in which he has waged his struggle, personifying in his conduct the words that were spoken to mankind:

Whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also!1

Fifty thousand Negroes obeyed this commandment in December, 1955, and won a victory. This was the beginning. At that time Martin Luther King was only twenty-six years old; he was a young man, but nevertheless a mature one.

His father is a clergyman, who made his way in life unaided and provided his children with a good home where he tried to shield them from the humiliations of racial discrimination. Both as a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and as a private citizen, he has been active in the struggle for civil rights, and his children have followed in his footsteps. As a boy Martin Luther King soon learned the role played by economic inequality in the life of the individual and of the community.

From his childhood years this left its indelible mark on him, but there is no evidence to suggest that as a boy he had yet made up his mind to devote his life to the struggle for Negro rights.

He spent his student years in the northern states, where the laws provided no sanction for the discrimination he had encountered in the South, but where, nevertheless, black and white did not mix in their daily lives. Yet living in the northern states – especially in a university milieu – was like a breath of fresh air. At Boston University, where he took a doctor’s degree in philosophy, he met Coretta Scott, who was studying singing. She was from his own state of Alabama, a member of the black middle class which also exists in the South.

The young couple, after being married, were faced with a choice: should they remain in the North where life offered greater security and better conditions, or return to the South? They elected to go back to the South where Martin Luther King was installed as minister of a Baptist congregation in Montgomery.

Here he lived in a society where a sharp barrier existed between Negroes and whites. Worse still, the black community in Montgomery was itself divided, its leaders at loggerheads and the rank and file paralyzed by the passivity of its educated members. As a result of their apathy, few of them were engaged in the work of improving the status of the Negro. The great majority were indifferent; those who had something to lose were afraid of forfeiting the little they had achieved.

Nor, as Martin Luther King discovered, did all the Negro clergy care about the social problems of their community; many of them were of the opinion that ministers of religion had no business getting involved in secular movements aimed at improving people’s social and economic conditions. Their task was “to preach the Gospel and keep men’s minds centered on the heavenly! ”

Early in 1955 an attempt was made to unite the various groups of blacks. The attempt failed. Martin Luther King said that “the tragic division in the Negro community could be cured only by some divine miracle!”

The picture he gives us of conditions in Montgomery is not an inspiring one; even as late as 1954 the Negroes accepted the existing status as a fact, and hardly anyone opposed the system actively. Montgomery was a peaceful town. But beneath the surface discontent smoldered. Some of the black clergy, in their sermons as well as in their personal attitude, championed the cause of Negro equality, and this had given many fresh confidence and courage.

Then came the bus boycott of December 5, 1955.

It looks almost as if the boycott was the result of a mere coincidence. The immediate cause was the arrest of Mrs. Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. She was in the section reserved for Negroes and was occupying one of the seats just behind the section set aside for whites, which was filled.

The arrest of Mrs. Parks not only aroused great resentment, but provoked direct action, and it was because of this that Martin Luther King was to become the central personality in the Negro’s struggle for human rights.

In his book Stride toward Freedom he has described not only the actual bus conflict, but also how, on December 5 after the boycott had been started, he was elected chairman of the organization formed to conduct the struggle.2

He tells us that the election came as a surprise to him; had he been given time to think things over he would probably have said no. He had supported the boycott when asked to do so on December 4, but he was beginning to doubt whether it was morally right, according to Christian teaching, to start a boycott. Then he remembered David Thoreau’s essay on “Civil Disobedience” which he had read in his earlier years and which had made a profound impression on him. A sentence by Thoreau3 came back to him:”We can no longer lend our cooperation to an evil system.”

But he was not convinced that the boycott would be carried out. As late as the evening of Sunday, December 4, he believed that if sixty percent of the Negroes cooperated, it would prove reasonably successful.

During the morning of December 5, as bus after bus without a single Negro passenger passed his window, he realized that the boycott had proved a hundred percent effective.

But final victory had not yet been won, and as yet no one had announced that the campaign was to be conducted in accordance with the slogan: “Thou shalt not requite violence with violence.” This message was given to his people by Martin Luther King in the speech he made to thousands of them on the evening of December 5, 1955. He calls this speech4 the most decisive he ever made. Here are his own words:

“We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and Justice.

But, [he continues] our method will be that of persuasion not coercion. We will only say to the people, “Let your conscience be your guide.” Our actions must be guided by the deepest principles of our Christian faith … Once again we must hear the words of Jesus5 echoing across the centuries: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, and pray for them that despitefully use you.”

He concludes as follows:

“If you will protest courageously and yet with dignity and Christian love, when the history books are written [in future generations], the historians will [have to pause and] say: “There lived a great people – a black people who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.” This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility.”

This battle cry – for such it was – was enthusiastically received by the audience. This was Montgomery’s moment in history, as Martin Luther King calls it.

His words rallied the majority of Negroes during their active struggle for human rights. All around the South, inspired by this slogan, they declared war on the discrimination between black and white in eating places, shops, schools, public parks, and playgrounds.

How was it possible to obtain such strong support?

To answer this question we must recall the strong position enjoyed by the clergy among the Negroes. The church is their only sanctuary in their leisure hours; here they can rise above the troubles and cares of everyday life. Nor would the appeal that they go into battle unarmed have been followed, had not the blacks themselves been so profoundly religious.

Despite laws passed by Congress and judgments given by the American Supreme Court, this struggle has not proved successful everywhere, since these laws and judgments have been sabotaged, as anyone who has followed the course of events subsequent to 1955 knows.

Despite sabotage and imprisonment, the Negroes have continued their unarmed struggle. Only rarely have they acted against the principle given to them by requiting violence with violence, even though for many of us this would have been the immediate reaction. What can we say of the young students who sat down in an eating place reserved for whites? They were not served, but they remained seated. White teenagers mocked and insulted them and stubbed their lighted cigarettes out on their necks. The black students sat unmoving. They possessed the strength that only belief can give, the belief that they fight in a just cause and that their struggle will lead to victory precisely because they wage it with peaceful means.

Martin Luther King’s belief is rooted first and foremost in the teaching of Christ, but no one can really understand him unless aware that he has been influenced also by the great thinkers of the past and the present. He has been inspired above all by Mahatma Gandhi6, whose example convinced him that it is possible to achieve victory in an unarmed struggle. Before he had read about Gandhi, he had almost concluded that the teaching of Jesus could only be put into practice as between individuals; but after making a study of Gandhi he realized that he had been mistaken.

“Gandhi” he says, “was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force …”

In Gandhi’s teaching he found the answer to a question that had long troubled him: How does one set about carrying out a social reform?

“I found” he tells us, “in the nonviolent resistance philosophy of Gandhi … the only morally and practically sound method open to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.”

Martin Luther King has been attacked from many quarters. Greatest was the resistance he encountered from white fanatics. Moderate whites and even the more prosperous members of his own race consider he is proceeding too fast, that he should wait and let time work for him to weaken the opposition.

In an open letter in the press eight clergymen reproached him for this and other aspects of his campaign. Martin Luther King answered these charges in a letter written in Birmingham Jail in the spring of 1963. I should like to quote a few lines:

“Actually time itself is neutral … Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts of men, willing to be co-workers with God, and without this hard work time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.”7

In answer to the charge that he has failed to negotiate, he replies:

“You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to … foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.”

He reminds them that the Negroes have not won a single victory for civil rights without struggling persistently to achieve it in a lawful way without recourse to violence. When reproached for breaking the laws in the course of his struggle, he replies as follows:

“There are two types of laws: just and unjust … An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law …

An unjust law is a code that a numerical or powerful majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself …

One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty.”

To read more visit:https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/ceremony-speech/